Wembley: May 1968. Even the flintiest man can cry. As Bobby Charlton clasps his boss tightly, his etiquette and decorum melt away. It is impossible to appreciate the cathartic nature of the moment entirely, but the grimace of relief etched across Manchester United’s number 9 is both palpable and haunting.

By now, England’s record goalscorer has only a few strands of hair to cover his balding head, and even less youthful exuberance to cover the torture and joy that is battling inside him. Matt Busby, the seemingly immovable rock at the heart of the club, the rigidly catholic and warmly compassionate Scotsman, reciprocates the emotional outpouring from his captain. Finally, a glorious vindication of an entire lifetime has been achieved; but even still, it is not complete.

Manchester United have just conquered the mighty Eusébio and his flamboyant Benfica 4-1 to claim the ultimate prize of all for the first time, more than a decade after first campaigning for it. The insular arrogance of the then Football League chairman Alan Hardaker threatened to derail the pioneering project before it began as he tried to block their entry into Europe in 1956, just as he had done to Chelsea the year before. He hadn’t foreseen the incredible vision and single-mindedness of Busby, however.

It is not complete because some people are missing. The words that speak through the embrace of a sweat-drenched Charlton and a tear-drenched Busby will never cease to be spoken, and they tell a tale of wonder, inspiration, tragedy, and rebirth. We will never know, but you can bet that one name edges to the front of their conscience, jostling his team-mates with him to whisper in Busby’s ear in his thick Black Country accent: “Chin up chief, we did alright didn’t we?”

That name is Duncan Edwards.

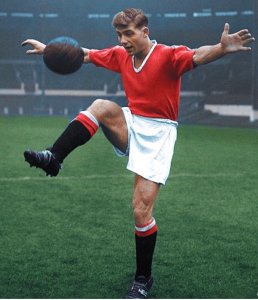

Belgrade, February 1958. With the away goals rule still the best part of a decade away, a 2-1 lead from the home leg is still a slender advantage to protect as the reds of Manchester strode out confidently onto the icy pitch in Yugoslavia. Immaculate, impressive, and confident: this is the epitome of what they should be, the realisation of their enormous potential, unafraid of anything life could throw at them. Still, it doesn’t hurt the others to see the colossal thighs and Adonis chest of their talismanic left-half bulging through his kit.

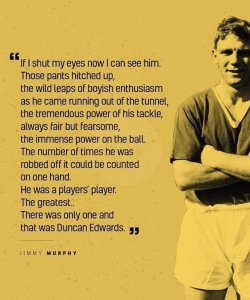

As Edwards puffs his chest out further while they wait for kick-off, a calm descends on the team that takes its lead from the man from Dudley. Now is not the time for one of Jimmy Murphy’s legendary tub-thumping team talks to pump their adrenalin through their veins; now is time to focus intently.

They needn’t have worried. Dennis Viollet silences the raucous crowd after only two minutes before a swift double from Charlton sends them into the break 5-1 up on aggregate. The high spirits soon seep away after the break though, as Red Star Belgrade hit back with three of their own inside 13 minutes of the second period, but the Mancunians hold on to book a second consecutive European semi-final.

Manchester, the next day. Whistling a cheery tune without a care in the world, Jimmy Murphy swans into his office at Old Trafford feeling on top of the world.

His team of youngsters, his children that he has nurtured from wide-eyed frail kids to men brimming with pride, are on their way back from their latest glorious victory in Europe, but Murphy couldn’t travel with them.

Alma George, the club secretary, hasn’t said a word, and it is only now that Murphy sees her distraught expression. She pulls herself together just enough to mumble the news that nobody could have prepared for: the boys have been involved in a horrific plane crash, and we’re not even sure how many are alive. Over a decade of living and breathing every step of their development has been cruelly taken from him in a simple sentence.

In a world of social media, tablets and those dreadful selfie sticks, it is hard to imagine crouching around an old wireless set for a brief headline for news, but that is what most of the country did in over the next few days. No instant notifications here; twice a day for over a fortnight, families huddled around to catch the BBC radio announcements from Dr. Georg Maurer of Munich Rechts der Isar hospital. Many rushed to the newsstand to pick up the evening editions, for the latest news about the horrific disaster at Munich Riem airport which had been carrying the buccaneering Manchester United side back home. One chilling Manchester Evening News headline simply read: “Matt 50-50; Edwards ‘Grave’; Berry Coma”.

Each day seemed to tell a different angle on the story of the fight for survival, but Duncan Edwards’ battle to overcome chronic kidney damage, crushed lungs and broken limbs shook the nation – here was a colossus who was not even near his prime, and yet strode across pitches as if he not just belonged, but deserved to take control. In one famous FA Youth Cup fixture away to Chelsea, Murphy had instructed his charges not to pass too much to Edwards for fear of depending on the man-child too much; after struggling to a 1-0 deficit at half time, he simply gave in and said, “Alright, just give it to Duncan”. Forty-five minutes later he was vindicated as Edwards, revelling in being at the centre of the match again, inspired his side to another final in the competition.

For someone as immovable and awe-inspiring as this, it seemed unthinkable that he could perish. The catastrophe was grim; the privately chartered Elizabethan twin-engine plane had failed to take off after two failed attempts, and had crashed disastrously into houses off the end of the runway, shredding the fuselage open and spilling its cargo across the snow. In the panic, survivors crawled to safety while attending to the unconscious Busby and desperately trying to help others, but Edwards had fared worst than most whose lives had not already been claimed.

In Munich, with seven of his teammates already among the dead, the doctors treating Edwards reckoned it was a miracle he survived as long as he did. They were devastating injuries: damaged kidneys, a collapsed lung, a broken pelvis, multiple fractures of his right thigh, crushed ribs and a litany of internal injuries.

Famously, he asked the assistant manager, Jimmy Murphy, during one period of semi-consciousness what time the kick-off would be for the game against Wolves the following Saturday. What does not get reported so much is that he also told Murphy he was desperate not to miss it. The initial casualty list had described him as “mortally injured” but his final breath came 15 days later. “It was as though a young Colossus had been taken from our midst,” Frank Taylor wrote in The Day a Team Died.

He was also the original Boy Wonder, the first player to create the kind of unfettered excitement that George Best, Paul Gascoigne, Ryan Giggs and Wayne Rooney brought later. One of the old newspaper reports I found researching this piece – from 1 April 1953 – is a few days before Edwards makes his first-team debut for United. The impression I had was that sportswriters of that generation were less prone to extravagant predictions than the modern-day journalist. Yet George Follows, writing for the News Chronicle, seems to be ahead of his time.

“Like the father of the first atom bomb, Manchester United are waiting for something tremendous to happen. This tremendous football force they have discovered is Duncan Edwards, who is exactly sixteen and a half this morning. What can you expect to see in Edwards? Well, the first important thing is that this boy Edwards is a man of 12st and 5ft 10ins in height. This gives him his first great asset of power. When he heads the ball, it is not a flabby flirtation with fortune, it is bold and decisive. When he tackles, it is with a man-trap bite, and when he shoots with either foot, not even Jack Rowley – the pride of Old Trafford – is shooting harder. Though nobody can tell exactly what will happen when Edwards explodes into First Division football, one thing is certain: it will be spectacular.”

As Busby said: “Duncan was never a boy, he was a man even when we signed him at 16.”

Busby’s eyes would twinkle apparently – initially with paternal affection, later with great sorrow – when the conversation was of the boy from Dudley. He would also say that “the bigger the occasion, the better he liked it” and Edwards certainly lived up to that reputation when England travelled to Berlin to face West Germany, the world champions, at the Olympic Stadium in 1956. His goal was a masterpiece, slaloming through a blockade of defenders before smashing the ball in from 25 yards and setting up a 3-1 win.

This time the eulogy came from the captain, Billy Wright: “The name of Duncan Edwards was on the lips of everyone who saw this match; he was phenomenal. There have been few individual performances to match what he produced that day. Duncan tackled like a lion, attacked at every opportunity and topped it off with that cracker of a goal. He was still only 19, but already a world-class player.”

A team of ‘bouncing Busby Babes’, the Flowers of Manchester, torn to shreds and brutally, mercilessly taken from everyone, and at the forefront, Big Dunc. It wasn’t just that he was so young, or that he represented England’s great hope – it is said Walter Winterbottom’s side would have been favourites in Sweden that summer with Edwards alongside Tommy Taylor and David Pegg. Nor was it his swagger; it was his humanity, his enormous personality, and his kind touch that connected him to so many.

So long, chief – it was great while it lasted.